The market last week hurt investors from coming and going.

The 5.3-percent crunch in the S&P 500 Wednesday and Thursday took the index back to early-July levels — inflicting buyer's remorse on anyone who bid into the late-summer rally — while punishing the most popular huge growth stocks of technology the hardest.

In mid-week, an ear-splitting consensus that bond yields would keep rising drove the largest one-day withdrawal from Blackrock's $53 billion flagship iShares Core U.S. Aggregate Bond ETF (AGG) Wednesday – just in time for bonds to rally and yields settle back a bit.

Then came Friday's rescue rally to thwart short-term traders' geared for a typical Friday flight from risk. The major indexes lost a tentative morning rally only to carry higher in the final hour of trading by 1.4 percent to recoup a quarter of the preceding two-day loss.

(Futures pointed to more selling on Monday.)

A week ago, the case was made here that Wall Street's bears had an openingto pressure the market in the short term, and they surely seized upon it. So with stocks down a quick 4 percent in a week in a way that confounded the crowd, which direction is the "pain trade" from here?

It's never an unambiguous call — and the market doesn't always take the path of maximum frustration for the greatest number of investors. But at the moment it still appears the pain trade is to the downside — or, perhaps most diabolically, up first and then down harder.

First, on Friday's comeback: It was impressive without being decisive. Stocks had quickly become substantially "oversold," the S&P stretched far below its trend and the vast majority of stocks primed for a bounce. The fact that the market responded to these conditions — that it "bounced when it had to" is a net positive.

Thursday's low, near 2710 for the S&P 500, is certainly a plausible short-term low for a trading rally that can recover more of the recent losses.

But the damage to the big-cap indexes happened too fast for trader sentiment to grow desperately fearful yet. And it seems there might be too many observers clinging to the logic that seasonal factors now turn positive and earnings season will bring relief.

And are investors fixating too much on the idea that this was mostly just a nasty shakeout of crowded momentum positions held by performance-chasing funds?

It certainly was partly that, but the scapegoating of mechanical/technical factors shows a refusal to grapple with the possibility that the market was either too overvalued or is responding to signs of genuine economic deceleration.

The wishful expectation expressed by many investors that rising yields are a trigger for a long-awaited shift from growth to value stocks faces a high burden of proof. Leadership transitions at this point in a cycle are unusual, and would seem to require a significant market-wide retrenchment rather than unfold as a harmless handoff.

At the start of last week, 54 percent of the S&P 500 was in the S&P 500 Growth index, and 46 percent lumped into value. The market's growth bet can't easily be unwound without a net drop in total market value.

For what it's worth, too, Wednesday the S&P 500 fell more than 3 percent, and of all the times the index has dropped by at least 3 percent in a day, about 80 percent came as part of a decline of 10 percent or more. At last week's low the index was a bit more than 7 percent below its Sept. 20 high. The bounces in bank and small-cap stocks - which were weak long before the major indexes buckled — were either non-existent or putrid Friday.

So, it's now a "Show me" market, one that can no longer be trusted to do just enough to keep grinding higher through fortuitous sector rotation, slightly more stocks rising that falling most days and the heavy lifting of select mega-cap growth darlings.

Jeff de Graaf of Renaissance Macro Research has been respectful of the market uptrend but on alert for a defensive turn in what he sees as a late-cycle environment.

On the path from here, with no clear capitulation but no obvious credit stress, he says, "It's a tough call...Currently, with credit sanguine, we're more confident in resumption of trend. Even if it is the beginning of the end, the playbook would be to see equities bounce further, challenge a new high (if not make one) before puking again."

Credit markets sending no serious warning signals yet about the economy is one big thing distinguishing this year from the 2007 peak, when the S&P made a marginal new all-time high in early October, before a quick reversal made it look like a "bull trap."

Of course, housing had been falling apart for more than a year by then and the Fed had long stopped tightening in response. So we should relish the big differences, while also recalling that market patterns rhyme.

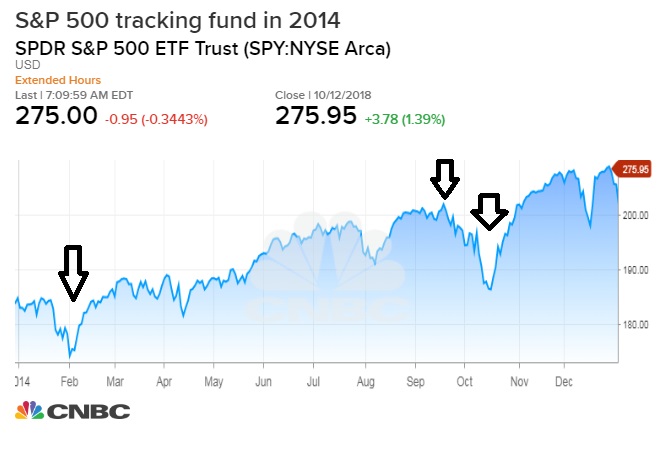

Another year is a bit more intriguing and less-discussed as a possible analogy for 2018. Starting in the first quarter I started citing the 2014 market as a possible map for this year:

Tweet

While 2014 didn't start as strong as 2018 did, both years had a February setback, were up around 2 percent at Memorial Day, made a record high in the third week of September for around a 9 percent year-to-date gain, then pulled back hard into mid-October. That October 2014 dump was blamed on a combination of Fed-tightening fears and the Ebola scare.

It recovered in a "V" pattern and powered to new highs through December to book an 11 percent annual gain - which most investors would take right now.

Of course, it closed that year essentially at the levels from which the market would collapse into a quasi-bear market in late 2015 into 2016 that would undercut the entire fourth-quarter 2014 rally.

Not an outright prediction, of course. But from that October gut check it was eventually a painful trade — up, then down.

No comments:

Post a Comment