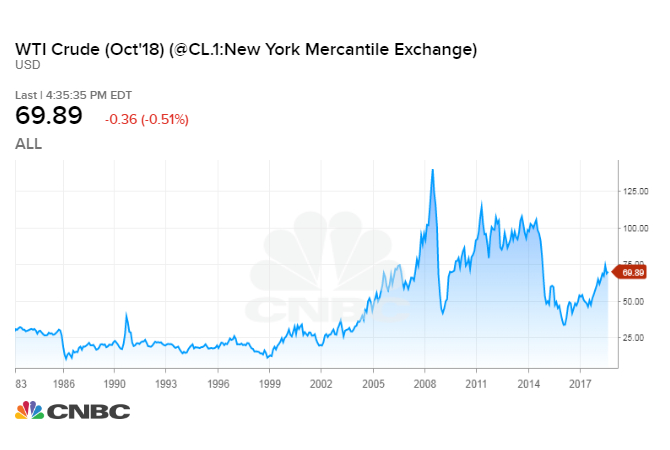

The collapse of Lehman Brothers 10 years ago marked the point of no return in the global financial crisis. But it also brought another crisis — a 4½-year surge in oil prices to all-time highs — to a screeching halt.

What it didn't do is end a remarkable period of boom and bust in the oil market.

It was a runaway train in the summer of 2008, until the global recession destroyed demand for energy and toppled crude from its all-time high above $147 a barrel. Today, some of the same factors that pushed oil prices to the stratosphere then are re-emerging, raising fresh concerns about another round of triple-digit oil prices.

The world's appetite for oil is growing at a brisk pace, yet oil companies have pulled back investments in big, long-life projects following a period of low prices. Geopolitics and production problems are capping output in some OPEC countries, and spare capacity in Saudi Arabia, in the world's top exporter, remains thin.

At the same time, the oil market has seen profound changes since 2008, and some of those transformations are putting downward pressure on the cost of crude.

As these forces work against each other, volatility is likely to stay.

When prices first broke out in 2003, countries beyond OPEC weren't doing much to help the cartel meet growing demand. Today, the United States is poised to become the world's top oil producer. Output has more than doubled since 2008, to 10.7 million barrels a day, fueled by a technology revolution that allows U.S. drillers to free oil and gas from shale rock.

The U.S. shale boom has largely put to bed concerns about "peak oil" — the theory that global oil production would soon enter a terminal decline, sending crude prices skyrocketing and plunging the world into crisis. Instead, the emergence of electric cars and efforts to mitigate climate change have forecasters trying to predict when demand for oil will peak.

In the long term, "peak demand" threatens to whittle away at the value of oil. But in the near term, expectations of peak demand are injecting fresh uncertainty into the market, according to Antoine Halff, the former chief oil analyst at the International Energy Agency.

"Those expectations I think run the risk, maybe paradoxically, of causing supply shortfalls and thus new price swings," he said. "Because if investors become concerned about stranded assets and declining values of oil, there's a risk that there's going to be insufficient investment to meet demand or that the cost of capital to provide investments will rise."

Oil companies already cut spending on exploration and production for the 2015 to 2020 period by about $1 trillion, according to energy research firm Wood Mackenzie.

"The market may become a little bit more volatile as we go forward and we might expect larger price swings," said Halff, who is now a senior research scholar at Columbia University's Center on Global Energy Policy.

That's a view shared by Robert McNally, president of Rapidan Energy Group and author of "Crude Volatility," a history of oil market spikes and crashes. In McNally's view, the market is locked in a period of boom and bust that started in 2003, when a confluence of factors ended a period of relative stability for oil prices.

One of his core arguments is that there's essentially no one behind the wheel of the oil market. The 15-nation oil cartel OPEC will periodically cut or boost output in times of emergency, but its de facto leader, Saudi Arabia, has not actively managed the market since 1985, he says.

That played a major role in the 2014 oil price crash. Right before the downturn, forecasters wrongly assumed OPEC would throttle back production as output from U.S. shale fields started to exceed expectations and oil demand unexpectedly softened.

While Saudi Arabia initially refused to cut output, oil's plunge from more than $100 a barrel in 2014 to less than $30 in 2016 sparked another major change in oil markets. Saudi Arabia and OPEC partnered with Russia and other producers beginning in 2017 to prop up prices by cutting production.

Some now believe the group will fill the long vacant role of market manager, but McNally is skeptical the alliance will last.

"The jury remains out on whether this new Saudi-Russian led entity will prove to be a successful long-term supply manager or instead join the list of ad hoc, temporary cartels formed after price busts but that dissolved afterward," McNally said in written testimony for a recent Congressional hearing on oil price volatility.

The Russia-Saudi alliance could soon be tested by another challenge: keeping prices from rising too much.

Oil prices have risen faster than anticipated in the first half of the year, hitting a 3.5-year high above $80. Strong demand and supply outages underpinned the rally, but deep-seated problems and geopolitical tension in OPEC countries also played a role.

Venezuela's production continues to slide as the country remains mired in a prolonged economic crisis. Libya's exports remain unreliable after several years of internal conflict, and Angola is showing signs of structural decline. In Iran, renewed U.S. sanctions threaten to take roughly 1 million barrels of the nation's supply off the market.

That setup is similar to the early 2000s, when production issues in OPEC countries raised questions about whether Saudi Arabia had enough spare capacity to meet rising demand.

"I think we're kind of back there and we should be concerned about it," Halff said.

New geopolitical risks are also emerging in the Middle East as the Trump administration uses oil sanctions to achieve broad policy goals in Iran, said Michael Cohen, head of energy markets research at Barclays.

Analysts warned that oil prices could hit fresh highs after Iran threatened to shut down the Strait of Hormuz, the world's busiest oil shipping lane, in response to U.S. sanctions.

Still, Cohen said it would take a "perfect storm" to push oil markets back above $100 a barrel, and that storm is unlikely to form. In his view, Saudi Arabia and Russia don't want oil prices to surpass $100, and OPEC has enough spare capacity to tamp down prices.

"Is it as significant as it was a year ago? No. But we shouldn't ignore the possibility and the willingness to keep prices from going too high too quick, which would arguably cut into their long-term demand prospects," he said.

Those demand prospects are shakier today because major oil importers like India have pared back fuel subsidies, leaving consumers more exposed to oil price spikes than they were in 2008, Cohen noted. That means demand might not hold up as well in the face of $100 oil, and a drop in consumption would typically put downward pressure on oil prices.

Lastly, while bottlenecks have somewhat slowed production in the nation's top shale field, the Permian basin, few expect the U.S. shale juggernaut to stop growing in the medium term.

"When you look at the availability of drillable locations in the Permian and the U.S. in general — discovered but unsanctioned projects — there's a lot of oil out there," Cohen said.

No comments:

Post a Comment